差不多半个世纪,我又见小时候的四只羊了-黄河西口古渡、娘娘滩记行。小时候,为了不卖掉小羊羔,就提高价格......

人,有时需要活在故事里,或许人就是为故事而活着,成长着,走动多了,故事也就多了,因为有一天我们终将老去!

戴欣明,字:动能,号:七大山人,丙申年腊月初一,创作于2016年12月29日,清晨

2016年10月初,动能智库-戴欣明工作室一行六人在黄河几字湾调研

来到山西省河曲县,城北黄河岸边的“西口古渡”考察,河水在这里是清澈的,岸边游人稀少,小城的宁静中,似乎听到了河水的湍急声。环顾四周,早已没有了走西口商人的喧嚣,只是庙宇的存在能够让人知道,曾经有很多人的灵魂在这里歇息过。

以现代人的视角,以及现代建筑的映衬下,边上的凉亭的简陋能够把仅有的一丝追忆打断。好不容易看到一位老乡,自然要问他还有什么地方值得去,他顺口就说,你们可以去娘娘滩!娘娘滩地方距离这里几公里远,传说西汉初年吕后专权,将薄太后及其子刘恒贬谪于此。其后刘恒称帝(汉文帝:前203年—前157年,汉高祖刘邦第四子,母薄姬,汉惠帝刘盈之弟,西汉第五位皇帝。),于滩上建娘娘庙,故名娘娘滩。娘娘滩位于河道中,面积近13公顷,是个“凸”形小岛,为塞上有名的小绿洲。据说人在岛上可以听到晋、陕、内蒙古三省、区的鸡鸣,古迹加上情趣更加让我们寻味而去。

2016年10月初,动能智库-戴欣明工作室一行六人在黄河几字湾调研

我们的兴致立即被点燃。走!

因为是秋季,一些树木有些泛黄,一些树木还是绿的,少了些风光秀美;穿梭着,时不时就能看到黄河水,水倒是有些浩荡的感觉,但空气中总能嗅到一股尘土的味道。

娘娘滩是个小岛,需要坐船才能过去。或许是中午的原因,没有人招呼我们,我们喊着嗓子叫了半天,从一个临时铁皮房中传出低沉的声音:“好。”

一会,来了个船夫,胖胖的,介于高兴与不高兴之间,黑黝黝的脸上平淡得很,需要我们的调侃才有了笑容。行头上看上去不是那么正规,一个竹竿,一个锈迹斑斑的铁皮船,一船来回要60元。我生活在大城市惯了,总是担心这么不正规的一次性收费,回来是否有人撑船回去!无奈,勇往直前吧,反正总是有办法回来的。

上岛以后,先看到的是偌大的游泳池,满目苍夷,餐饮店已经不再营业了,到处是荒芜的景象。

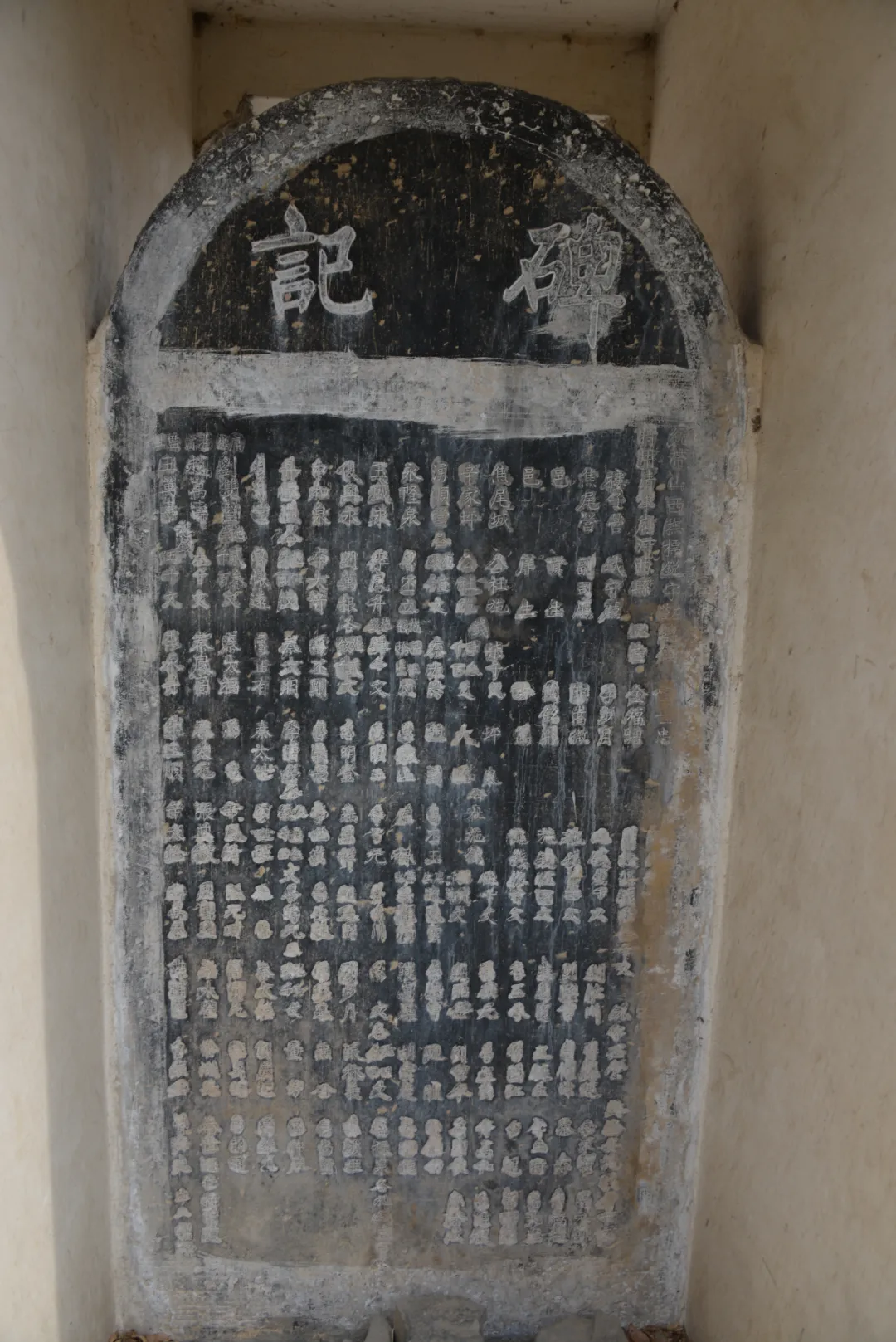

逆时针走了一阵子,可算见到了娘娘庙,建筑是现代的,对着黄河主航道,不大的庙,只有一个和尚打理日常的事务,攀谈中了解,他是这个村上的人,每每有人来上香,他就放些录制好的佛经,也让娘娘庙的的环境立马肃穆起来。虽然有些碑刻,但都是改革开放之后的捐资修建者的名字,只能在庙门不远处的一个石碑底座上看出些历史的痕迹,是个千年龟。虽然没有了石碑,但是从基座的花纹上能够看出有几百年以上的历史。看着这个石座,有点孤寂。

其实,这里只剩下了故事,远去的,以及即将到来的。

回来途中,走过几幢树木掩映下的老房子,看上去像解放前的房子,打听之后知道,一些事解放前的,一些是五十年代的,房子中只有老人在看家。走过一幢房子,看到一位80多岁的老人侧躺在炕上,样子与撑船的伙计有点像,特别是胖瘦,我突然知道她就应该是为我们撑船的人的母亲,后来也证实了。再走过去,发现了让我永远不会忘的场景,一个对于我来说介乎于神奇的场景:一个简单的栅栏里面有一只母羊,三只小羊在目不转睛地看着我。之所以神奇,是因为我看到了我小时候父母养的四只羊仿佛又出现在我的面前。

小时候城市里可以养猪、养羊,养猪是为了吃紧俏的猪肉,养羊是为了喝羊奶,好像很少有汉人吃羊肉、牛肉。据父亲戴联鹰说,那时候有七年的时间,城市人有条件的可以养牲畜。

其实,一方面是买不起,二是在国营商店里,牛羊肉只供应给回族人,并且要凭票,偶尔在路边上有人卖牛羊肉,还有马肉,我只会在那里溜溜圈。

70年代初期,听大人讲,有卖过人----肉的,被抓起来了,枪----毙了!无从考证,或许是大人吓唬小孩子的把戏。父亲为了改善家里的生活质量,买过几次猪来养,完全是村里面的做法,从小猪一直喂到大,过年的时候就有肉吃了。买羊是头一次,也是唯一的一次,因为随后的一年,城市里的居民不能饲养猪羊这些大动物,兔子、鸡鸭鹅还是可以养的。父亲买的是一只母羊,买回来没有多久就生了三只小羊,买的时候知道,因为这样的羊才会有奶。我是看着母羊把三只小羊生下来的。当时天快暗下来,我听到了羊在叫,过去看,牠在那里走动,第一只出生的时候,我正好去干什么去了,过去再看的时候,母羊在舔小羊。母羊来不及舔完第一只小羊,第二只就出生了,牠赶紧去舔第二只,应该是要把包衣马上舔下来,小羊羔才能喘气,没多久,第三只也出生了,牠不停的在舔,吃下那些包裹着小羊羔的胎盘,……忙的很。

1984年夏天,戴欣明父亲戴联鹰在吉林市龙潭区汉阳街十三委五组的平房家里,来了两车煤,准备弄煤坯过冬用。这个时候早已经有煤气罐了,但是很贵,烧炕还得用煤。

这时,家里有两个平房的房子,各40多平方米,后院被占用了,前院各有50多平方米。这是时,戴欣明在上大学。

这个房子的墙外面就是汉阳街,父亲戴联鹰背后。后面那堵墙是城市的“穿衣戴帽”做的,小时候没有。

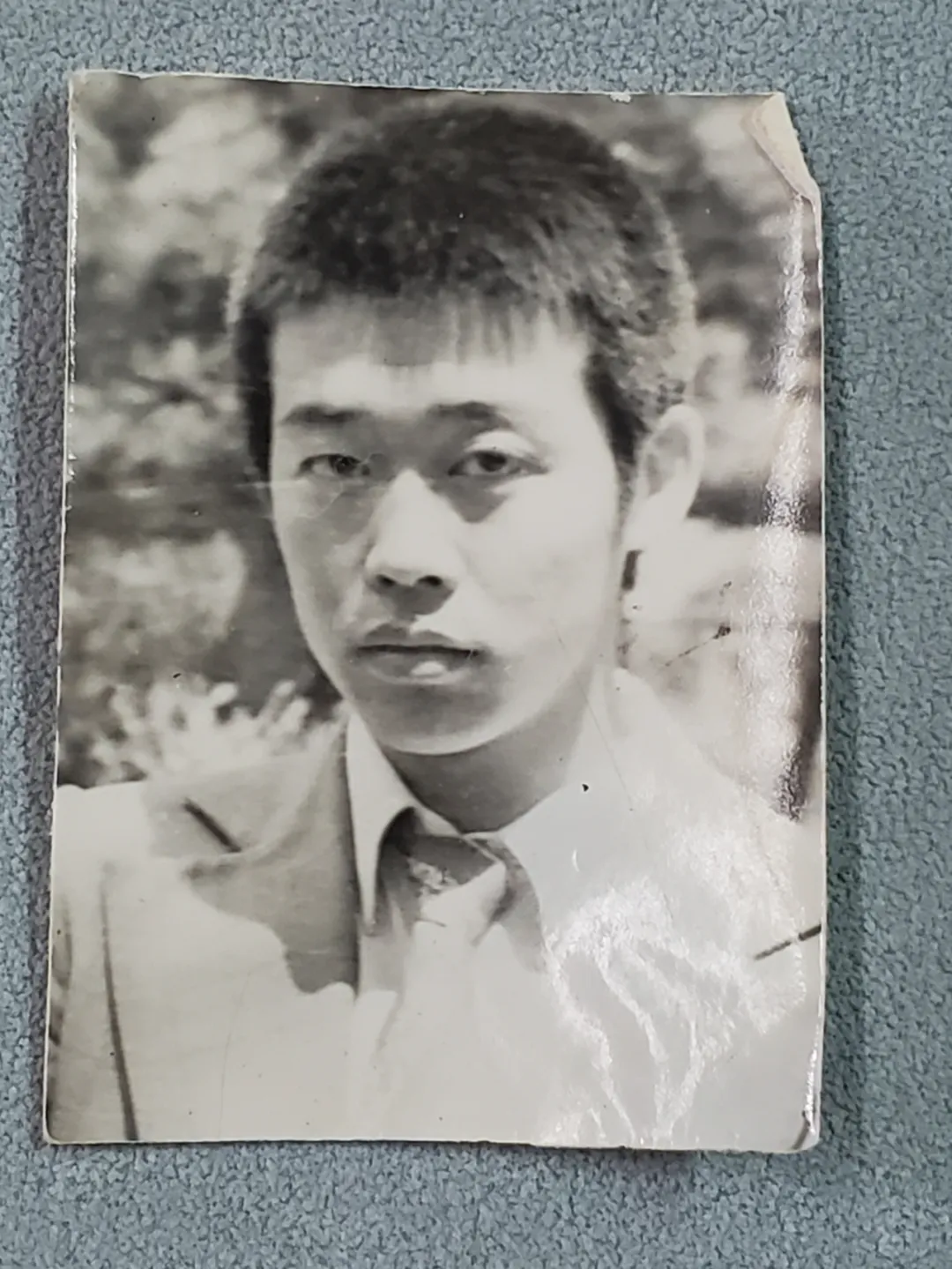

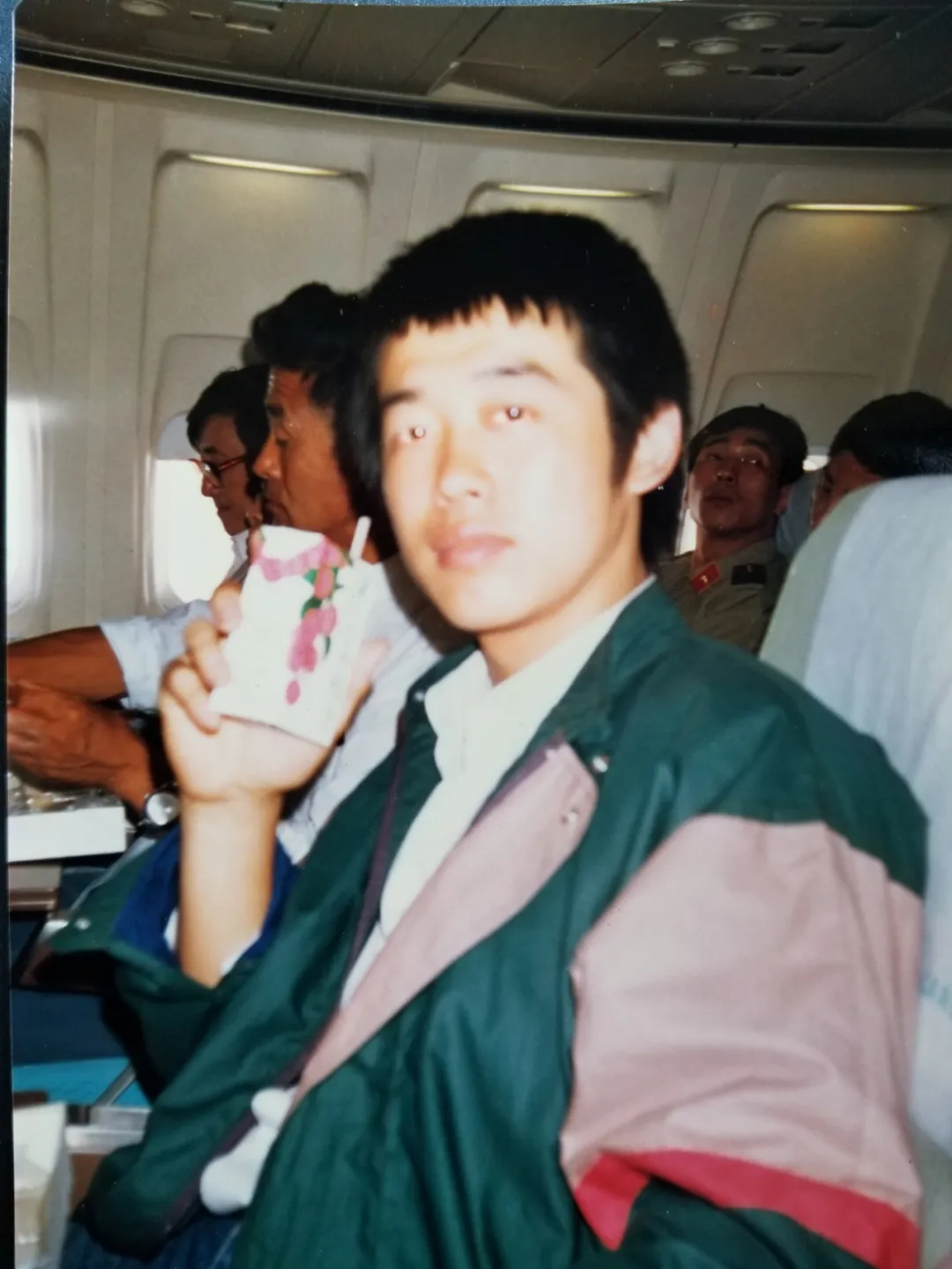

戴欣明在大学时,1986年春天,穿着香港进口西服,港商送的。

很快,我们家也喝上了羊奶。时不时我去挤羊奶,喂羊……

小羊也要喝奶的,要找到人家养,所以,我被指派去了棋盘街,蹲在集市的一角卖小羊,3元一只(当时一般家庭,双职工一个月的工资约八九十元),人来人往,有人问价。阳光很足,我是迎着光坐着,我完全看不清楚要买羊的人,我有点担心自己被卖掉。还有,我也很不好意思在那里卖,也有不想卖掉的意思,最终我还是把小羊羔抱了回来,之后羊如何离开我们家的就不知道了,似乎那些不是小孩子要知道的事情。

记得当时一直没有与父母交流过,似乎大家有默契,最终母羊还是卖了。来人牵走羊的时候,母羊一步一回头,咪咪的叫着,一幅依依不舍的样子,这个样子一直缠绕在我的脑海了直到现在我还时不时地想起来:“牠要去哪里哪?!”。

在娘娘滩一看到这只母羊,三只小羊,让我的记忆又连上了!原来牠们在这哪!

2016年10月初,动能智库-戴欣明工作室一行六人在黄河几字湾调研

人,有时需要活在故事里,或许人就是为故事而活着,成长着,走动多了,故事也就多了,因为有一天我们终将老去!

戴欣明,字:动能,号:七大山人

丙申年腊月初一,2016年12月29日,清晨

这是一篇老文章。2025年9月,也就是上个月和妈妈聊天的时候,也说起了这一段。我就很好奇,当时杀猪都是过年的时候吗?其实不是,有了猪可养的时候,到了冬天差不多就杀猪了。因为这个时候需要肉吃,也因为东北很冷,储存起来也很容易。

After Almost Half a Century, I Saw the Four Sheep from My Childhood Again – A Journey to Xikou Ancient Ferry and Niangniang Shoal on the Yellow River

By Dai Xinming

When I arrived at Xikou Ancient Ferry on the bank of the Yellow River north of Hequ County, Shanxi Province, for a survey, the river water here was clear, and there were few tourists by the bank. Amid the tranquility of this small town, I seemed to hear the rushing sound of the river. Looking around, the hustle and bustle of the merchants who once traveled westward to make a living (a historical phenomenon known as "Zou Xikou," where people from Shanxi, Shaanxi, and other regions moved west to the Inner Mongolia Plateau for survival and business) had long faded away. Only the existence of temples reminded people that countless souls once rested here.

From a modern perspective, and against the backdrop of contemporary buildings, the shabbiness of the nearby pavilion shattered the little trace of nostalgia left. Finally, I met a local villager and naturally asked him if there were any other places worth visiting. He casually replied, "You can go to Niangniang Shoal!" Niangniang Shoal is a few kilometers away from here. According to legend, in the early years of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 8 AD), when Empress Lü seized power, she exiled Empress Dowager Bo and her son Liu Heng to this place. Later, Liu Heng ascended the throne as Emperor Wen of the Western Han Dynasty (203 BC – 157 BC, the fourth son of Liu Bang, Emperor Gaozu of the Han Dynasty, whose mother was Consort Bo, and the younger brother of Liu Ying, Emperor Hui of the Han Dynasty; he was the fifth emperor of the Western Han Dynasty). A temple dedicated to Empress Dowager Bo (Niangniang Temple) was built on the shoal, hence the name "Niangniang Shoal." Located in the middle of the river channel, Niangniang Shoal is a convex-shaped islet covering an area of nearly 13 hectares, and it is a well-known small oasis in the northern frontier. It is said that on the islet, one can hear the crowing of roosters from three provinces/municipalities: Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Inner Mongolia. The combination of historical relics and such interesting folklore made us eager to explore it.

Our enthusiasm was immediately kindled. Let’s go!

It was autumn, so some trees had turned yellow while others remained green, making the scenery less beautiful. As we traveled, we caught glimpses of the Yellow River from time to time; the river looked mighty, but there was always a smell of dust in the air.

Niangniang Shoal is an islet, so we needed to take a boat to get there. Maybe it was noon, but no one came to greet us. We shouted for a long time, and a low voice came from a temporary iron-sheet house: "Okay."

Soon after, a boatman arrived. He was chubby, with an expression somewhere between pleasure and displeasure, and his dark face looked indifferent. It took some banter from us to make him smile. His gear didn’t look formal at all – just a bamboo pole and a rusty iron boat. The round trip cost 60 yuan. Accustomed to living in a big city, I couldn’t help worrying: with such an informal one-time payment, would there be someone to row us back? But there was no other choice; we had to move forward. After all, there must be a way to get back.

After boarding the islet, the first thing we saw was a large, dilapidated swimming pool. The restaurants had stopped operating, and desolation could be seen everywhere.

We walked counterclockwise for a while and finally found Niangniang Temple. The building was modern and faced the main channel of the Yellow River. It was a small temple, managed daily by only one monk. During our chat, we learned that he was from the village nearby. Whenever someone came to burn incense, he would play pre-recorded Buddhist scriptures, which immediately filled the temple with a solemn atmosphere. Although there were some stone inscriptions, they only recorded the names of donors who contributed to the temple’s reconstruction after the reform and opening-up period. The only trace of history could be found on the base of a stone stele not far from the temple gate – it was a thousand-year-old stone tortoise (a common base for steles in ancient Chinese architecture, symbolizing longevity and stability). Although the stele itself was gone, the carvings on the base showed that it had a history of hundreds of years. Looking at this stone base, I felt a sense of loneliness.

In fact, only stories remained here – those from the distant past and those yet to come.

On the way back, we passed several old houses hidden among trees. They looked like buildings from before the founding of the People’s Republic of China (1949). Upon inquiry, we learned that some were indeed from before 1949, while others were built in the 1950s. Only elderly people stayed in these houses to look after them. Passing one house, we saw an elderly person in their 80s lying on a kang (a traditional Chinese heated brick bed) sideways. They looked similar to the boatman, especially in body shape. Suddenly, I realized this must be the boatman’s mother – and this was later confirmed. Walking further, we came across a scene I would never forget, one that felt almost magical to me: inside a simple fence, there was one ewe and three lambs, all staring at me intently. It felt magical because it was as if the four sheep my parents had raised when I was a child had reappeared before my eyes.

When I was a child, people in cities could raise pigs and sheep. Pigs were raised for pork, which was in short supply at that time, and sheep were raised for goat’s milk. It seemed that few Han people ate mutton or beef back then. According to my father, Dai Lianying, there was a seven-year period when urban residents who had the means could raise livestock.

In fact, on one hand, people couldn’t afford mutton or beef; on the other hand, in state-owned stores, mutton and beef were only supplied to the Hui people (a Chinese ethnic group that traditionally consumes beef and mutton) and required coupons. Occasionally, someone would sell mutton, beef, or even horse meat by the roadside, but I would only walk around and look, never buying.

In the early 1970s, I heard adults say that someone had sold human flesh, was arrested, and then executed by firing squad. I have no way to verify if this was true – maybe it was just a trick adults used to scare children. To improve our family’s living conditions, my father bought pigs several times to raise, following the same method as in villages: he raised the pigs from piglets to full size, and then we would have pork to eat during the Chinese New Year. Buying sheep was the first and only time he did so, because the following year, urban residents were no longer allowed to raise large animals like pigs and sheep – only small ones like rabbits, chickens, ducks, and geese. The sheep my father bought was an ewe. Soon after bringing her home, she gave birth to three lambs – he had known she was pregnant when he bought her, as that was the reason she could produce milk. I watched the ewe give birth to the three lambs. It was getting dark, and I heard the ewe bleating. When I went to check, she was pacing around. I happened to be away when the first lamb was born; when I came back, the ewe was licking the lamb. Before she could finish licking the first lamb, the second one was born, so she hurried to lick the second one – presumably to remove the fetal membrane immediately so the lamb could breathe. Soon after, the third lamb was born, and she kept licking, even eating the placenta that wrapped the lambs… She was so busy.

Soon after, our family started drinking goat’s milk. From time to time, I would help milk the ewe and feed the sheep…

The lambs also needed to be fed, so we had to find someone to raise them. I was assigned to go to Qipan Street, where I squatted in a corner of the market to sell the lambs – 3 yuan each (at that time, the monthly salary of a two-income family was about 80 to 90 yuan). There were many people passing by, and some asked about the price. The sun was shining brightly, and I was sitting facing the sun, so I couldn’t see the faces of the people who wanted to buy the lambs clearly. I even worried that I might be sold myself. Besides, I felt embarrassed to sell them there, and part of me didn’t want to sell them at all. In the end, I took the lambs back home. Later, I never found out what happened to the sheep – it seemed like something children didn’t need to know.

I remember I never talked about this with my parents, but we seemed to have a silent understanding. In the end, the ewe was still sold. When the buyer led her away, the ewe looked back step by step, bleating softly, showing a reluctant demeanor. This scene has lingered in my mind to this day, and I still sometimes wonder: "Where was she going?!"

The moment I saw this ewe and her three lambs on Niangniang Shoal, my memories were reconnected! So this is where they’ve been!

Sometimes, people need to live in stories; perhaps we live for stories, grow through them, and accumulate more stories as we travel. For one day, we will all grow old!

Dai Xinming, style name: Dongneng, literary name: Qidashanren

The first day of the twelfth lunar month in the Bingchen Year (December 29, 2016), early morning

This is an old article. In September 2025, just last month, I talked about this period of time with my mother. I was curious: did people always kill pigs during the Chinese New Year back then? As it turned out, no. Whenever people had pigs to raise, they would kill them around winter. This was not only because they needed meat at that time, but also because the weather was extremely cold in the Northeast, making it easy to preserve the meat.